R.E.P.O. – Bureaucratic Horror, Procedural Fear, and the Violence of Retrieval

Introduction: Horror Framed as a Job

R.E.P.O. does not begin with screams, monsters, or apocalyptic stakes. It begins with employment. You are not a hero, not a survivor, not a chosen one. You are a worker. Your task is simple, clinical, and disturbingly mundane: retrieve objects from hostile environments and bring them back intact. The horror of R.E.P.O. does not come from what you fight—it comes from what you are expected to endure as part of routine labor.

This framing is what separates R.E.P.O. from most contemporary horror games. It does not rely on narrative exposition or cinematic tension. Instead, it weaponizes repetition, risk management, and the quiet cruelty of procedural objectives. This review examines R.E.P.O. as a systems-driven horror experience, focusing on how procedural spaces, fragile objectives, and economic pressure reshape fear into something methodical and deeply unsettling.

Quick Info (Overview Box)

Release Year: 2024

Genre: Cooperative horror / Extraction-based survival

Platforms: PC

Game Modes: Online co-op

Target Audience: Players who enjoy procedural horror, high-risk cooperation, and tension built through systems rather than scripted scares

1. Core Design Philosophy: Horror as Logistics

The central idea of R.E.P.O. is brutally efficient: fear is not created by monsters alone, but by logistical obligation. You are not exploring for curiosity or survival—you are retrieving assets under threat.

Objects matter. They are fragile, valuable, and often cumbersome. Dropping one can mean failure. Losing one can erase progress. Suddenly, fear is not abstract—it is attached to cargo.

This transforms horror into a planning problem. Every step is evaluated not just for safety, but for risk to the objective. The game turns anxiety into a cost-benefit analysis.

2. Retrieval Over Survival

Unlike traditional horror games where staying alive is the primary goal, R.E.P.O. complicates survival by making it secondary to completion. You can escape—but without the item, escape is meaningless.

This inversion changes player behavior. Risk-taking becomes necessary. Caution becomes expensive. The safest path is often the wrong one.

The game forces players to move toward danger, not away from it. Fear escalates not because you are hunted—but because you must keep going.

3. Procedural Spaces and Unreliable Memory

Levels in R.E.P.O. are procedurally generated, which undermines spatial mastery. Familiarity is temporary. Routes change. Landmarks lose reliability.

This prevents players from developing comfort through repetition. Even experienced players must re-learn environments every session.

The result is persistent vulnerability. Knowledge helps—but never guarantees safety. Procedural design ensures that fear cannot be fully optimized away.

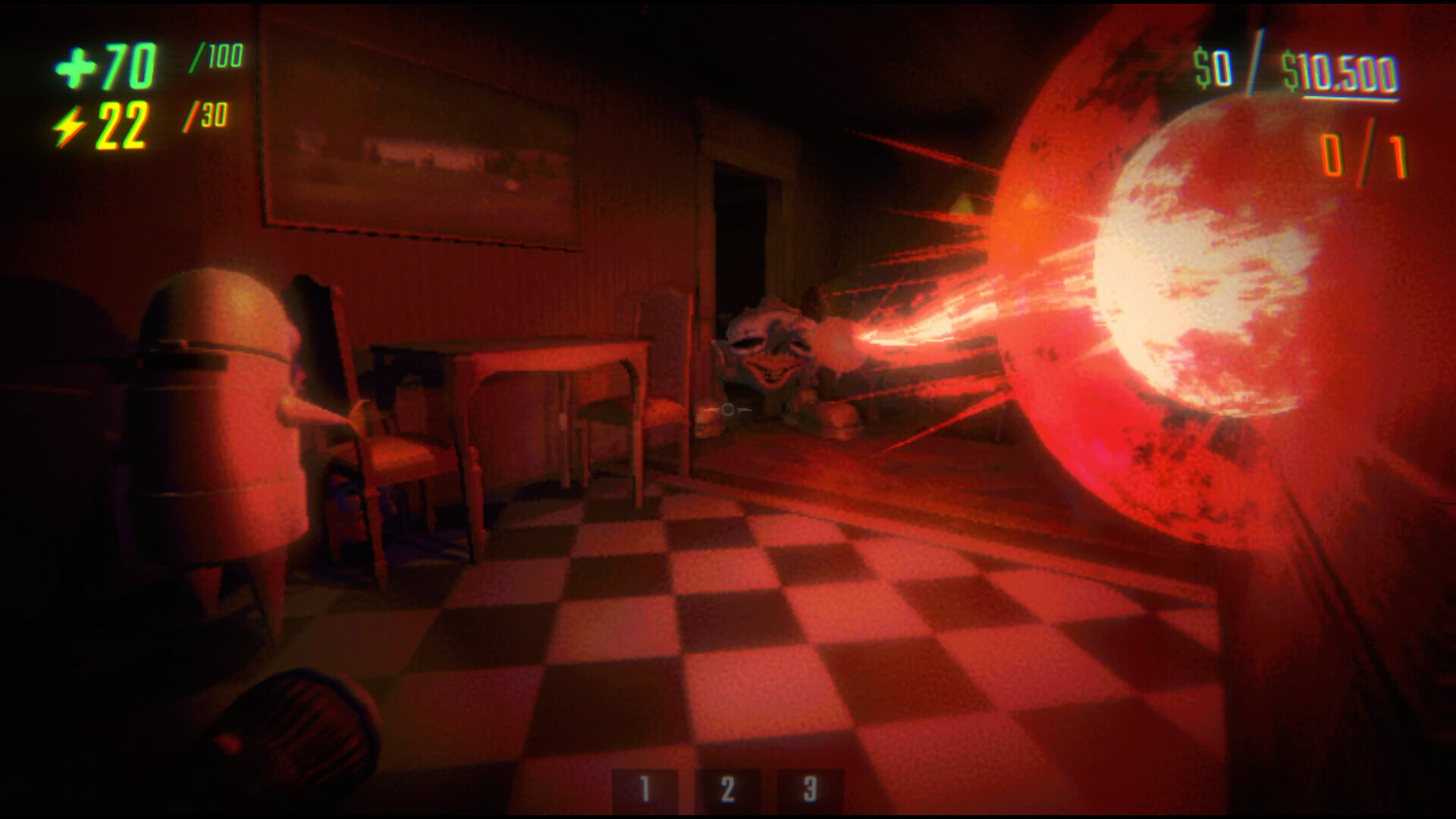

4. Environmental Threat Without Constant Presence

R.E.P.O. does not overwhelm players with constant enemies. Instead, it allows long stretches of quiet where nothing happens—and then punishes complacency.

Threat is ambient rather than aggressive. Sounds, lighting, and movement suggest danger without confirming it. Players are left to fill gaps with imagination.

This restraint is critical. By spacing encounters, the game allows tension to build organically. Fear grows during silence, not action.

5. Cooperative Fragility

In co-op, R.E.P.O. becomes a study in shared stress. Tasks require coordination: carrying objects, covering angles, managing movement speed.

One mistake affects everyone. A dropped item. A mistimed sprint. A miscommunication. Failure is collective.

This shared vulnerability strengthens tension. Players are not just afraid of dying—they are afraid of letting others down. The game exploits social pressure with surgical precision.

6. Objects as Emotional Anchors

The retrieved items in R.E.P.O. become emotional anchors. Players develop attachment not because of narrative, but because of effort invested.

Carrying an object through danger creates stakes. The longer you hold it, the more terrifying failure becomes. Dropping it feels personal.

This is a powerful psychological loop. The game makes players care deeply about meaningless objects—because the system demands it.

7. Sound Design and Spatial Uncertainty

Audio in R.E.P.O. is understated but precise. Footsteps echo unpredictably. Environmental noises blur into potential threats.

The lack of clear audio signals forces interpretation. Is that sound environmental—or hostile? Did something move, or was it imagination?

This ambiguity keeps players mentally exhausted. Constant interpretation drains confidence, making mistakes more likely over time.

8. Economy of Risk

Progression in R.E.P.O. is tied to successful retrievals. Failure has lasting consequences. Lost items mean lost advancement.

This introduces an economic layer to horror. Players calculate risk not just in terms of survival, but in future capability. Do you push further now, or retreat and preserve what you have?

This long-term pressure transforms individual missions into chapters of a larger survival narrative authored by player decisions.

9. Player Psychology: From Fear to Resignation

One of R.E.P.O.’s most disturbing achievements is how it reshapes fear over time. Early sessions are filled with panic and hesitation. Later sessions feel colder.

Players stop asking, “Is this safe?” and start asking, “Is this worth it?” Fear does not disappear—it becomes instrumental.

This emotional shift mirrors real-world burnout. Horror gives way to grim efficiency. The game subtly critiques labor systems without ever stating it outright.

10. Limitations and Design Trade-Offs

R.E.P.O. is not universally approachable. Its tension is slow, its systems demanding, and its feedback intentionally sparse.

Players seeking constant action or narrative clarity may find it frustrating. Sessions can feel punishing, especially with uncoordinated teams.

However, these limitations are inseparable from its identity. R.E.P.O. does not aim to comfort—it aims to condition.

Pros

Innovative horror built on retrieval and logistics

Strong procedural replayability

High psychological tension through system pressure

Meaningful cooperative dependency

Minimalist design enhances atmosphere

Cons

Steep learning curve

Heavy reliance on teamwork and communication

Sparse narrative may feel opaque

Can be emotionally exhausting

Not suited for solo or casual play

Conclusion: Horror as Occupational Hazard

R.E.P.O. is not about defeating evil. It is about enduring systems that treat danger as routine and loss as acceptable overhead. It transforms horror into labor—and labor into horror.

For players who appreciate systemic tension, cooperative stress, and experiences that linger psychologically rather than visually, R.E.P.O. offers something rare and unsettling. It does not scare you with monsters. It scares you with expectations.