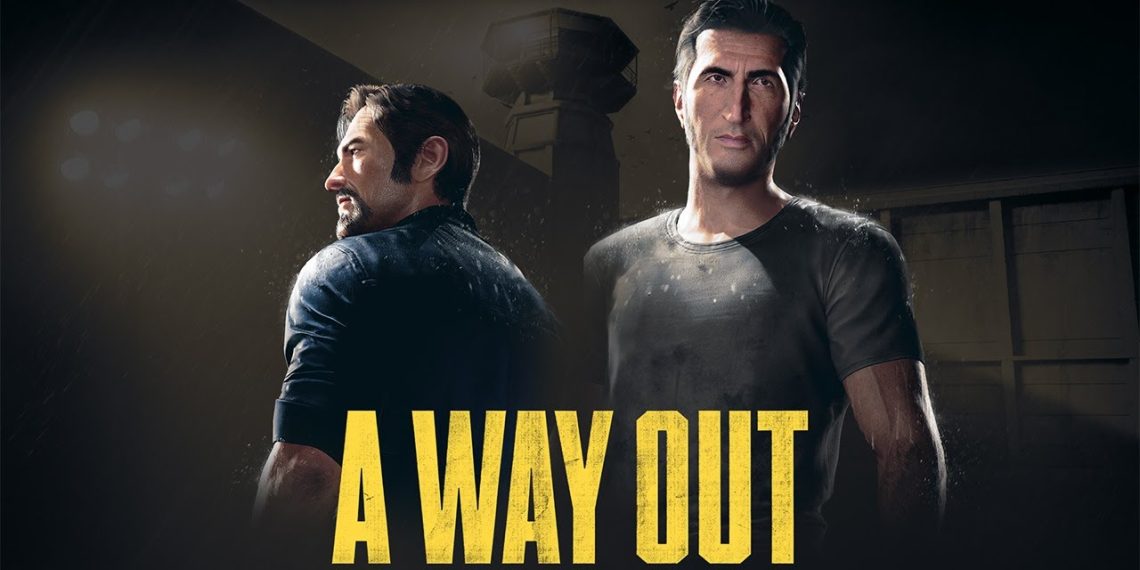

A Way Out – Shared Agency, Moral Friction, and the Fragility of Trust in Cooperative Storytelling

Introduction: A Game That Only Exists Between Two People

A Way Out is not simply a cooperative game. It is a design statement about interdependence. From the moment it begins, A Way Out makes one rule clear and unbreakable: this story cannot be experienced alone. Every mechanic, every narrative beat, and every emotional turn is constructed around the assumption that two human beings are present—communicating, negotiating, and sometimes disagreeing.

Unlike traditional co-op games that allow players to share space while pursuing individual goals, A Way Out binds players into a single dramatic structure. Progress is impossible without coordination. Meaning is impossible without empathy. This review examines A Way Out as a landmark experiment in cooperative narrative design, focusing on how shared control, moral ambiguity, and enforced collaboration reshape what storytelling in games can be.

Quick Info (Overview Box)

Release Year: 2018

Genre: Cooperative narrative adventure

Platforms: PC, PlayStation, Xbox

Game Modes: Mandatory two-player co-op (online or local)

Target Audience: Players who value story-driven experiences, emotional engagement, and cooperative play rooted in communication rather than mechanics

1. Core Design Philosophy: Co-op as a Narrative Requirement

The defining decision behind A Way Out is its refusal to offer a single-player mode. This is not a limitation—it is the point. The game is designed around the idea that some stories require more than one perspective.

Every scene is built with dual presence in mind. While one player acts, the other waits, observes, or supports. Sometimes both are active simultaneously, performing different tasks that converge into a single outcome.

This structure turns cooperation from a feature into a narrative language. The story does not merely include two characters—it depends on two players to function.

2. Split-Screen as Storytelling Tool

A Way Out uses persistent split-screen not as a technical necessity, but as a storytelling device. Players are constantly aware of what the other character is doing, even when their actions differ.

This creates parallel tension. One player may be engaged in a high-stakes interaction while the other performs a mundane task. The contrast builds suspense without relying on cutscenes.

The split-screen reinforces the idea that no perspective is complete. What you see is only part of the truth—just as in real relationships.

3. Character Duality: Leo and Vincent

The protagonists of A Way Out, Leo and Vincent, are deliberately contrasted. Leo is impulsive, emotionally driven, and reactive. Vincent is reserved, cautious, and controlled.

These differences are not cosmetic—they shape gameplay moments and narrative tone. Players often find themselves embodying their character’s mindset, even if it conflicts with their own instincts.

This alignment between character and player creates subtle role-play. Players do not just control Leo or Vincent—they become complicit in their worldview.

4. Mechanics as Emotional Glue

Mechanically, A Way Out is simple. Movement, interaction, quick-time events, and light puzzles dominate the experience. Complexity is intentionally minimized.

This simplicity serves a purpose. By reducing mechanical friction, the game ensures that attention stays focused on communication and emotional context rather than execution.

The challenge is not how to do something—it is when, together, and why. Mechanics become connective tissue rather than obstacles.

5. Cooperation Through Asymmetry

Many sections of A Way Out rely on asymmetrical cooperation. One player distracts guards while the other sneaks. One drives while the other shoots. One listens while the other speaks.

This asymmetry reinforces dependence. Neither player is more important, but neither is self-sufficient. Success requires awareness of the other’s situation.

Importantly, failure is often shared. Mistakes feel collective, reinforcing emotional accountability rather than individual blame.

6. Pacing and Emotional Rhythm

A Way Out’s pacing alternates between tension and intimacy. High-stress escape sequences are followed by quiet moments of conversation, reflection, or mundane activity.

These pauses matter. Playing darts, fishing, or sitting silently together may seem trivial, but they build emotional texture. They humanize characters and players alike.

The game understands that emotional investment grows not only through conflict, but through shared stillness.

7. Moral Ambiguity and Player Alignment

As the story unfolds, A Way Out introduces moral ambiguity without explicit judgment. Characters make questionable decisions. Motivations clash. Truth is partial.

Players are not asked to choose “right” or “wrong.” Instead, they are asked to understand—and sometimes disagree with—their character’s choices.

This creates tension between players. Conversations spill beyond the screen. Moral alignment becomes a topic of real discussion, not menu selection.

8. The Ending: Betrayal as Design, Not Twist

Without spoiling specifics, A Way Out’s final act reframes the entire experience. What initially feels like a cooperative escape story transforms into something far more confrontational.

The game does not ask permission to do this. It assumes that trust has been built—and then tests it. Mechanics that once encouraged cooperation are repurposed to create conflict.

This is not a shock ending—it is a logical consequence of everything that came before. The emotional impact is powerful precisely because it involves another real person.

9. Player Psychology: Trust, Complicity, and Loss

One of A Way Out’s greatest achievements is how it manipulates player psychology. Trust is built through hours of cooperation. Dependence becomes habitual.

When that trust is challenged, the response is visceral. Players feel betrayal not as spectators, but as participants. The emotional reaction is personal.

Few games manage to make players feel complicit in narrative outcomes. A Way Out does this by ensuring that no one is innocent—not even the players.

10. Limitations and Structural Risks

A Way Out’s focused design comes with limitations. Replay value is low once the story is known. Mechanical depth is intentionally shallow.

The experience also depends heavily on player chemistry. A disengaged or incompatible partner can undermine immersion.

However, these risks are inseparable from the game’s ambition. A Way Out chooses specificity over flexibility—and accepts the consequences.

Pros

Innovative mandatory co-op storytelling

Strong emotional impact driven by player interaction

Effective use of split-screen as narrative device

Clear character contrast enhances role-play

Memorable, discussion-provoking conclusion

Cons

Limited replayability

Minimal mechanical depth

Requires a committed second player

Not suitable for solo or drop-in play

Narrative impact depends on player engagement

Conclusion: A Game That Exists Only Once

A Way Out is not designed to be replayed endlessly, optimized, or mastered. It is designed to be shared, experienced, and remembered.

By tying narrative meaning directly to cooperation and trust, it achieves something rare: a story that cannot exist without human presence. Not NPCs. Not AI. Real people, sitting together, making decisions.

For players willing to engage emotionally and communicate openly, A Way Out offers a singular experience—one that lingers not because of its mechanics, but because of the relationship it creates and ultimately tests.

It is not a game about escape.

It is a game about what happens

when two people try to escape together.