PEAK – Vertical Risk, Cooperative Trust, and the Psychology of Climbing Together

Introduction: Progress Is Measured in Height, Not Power

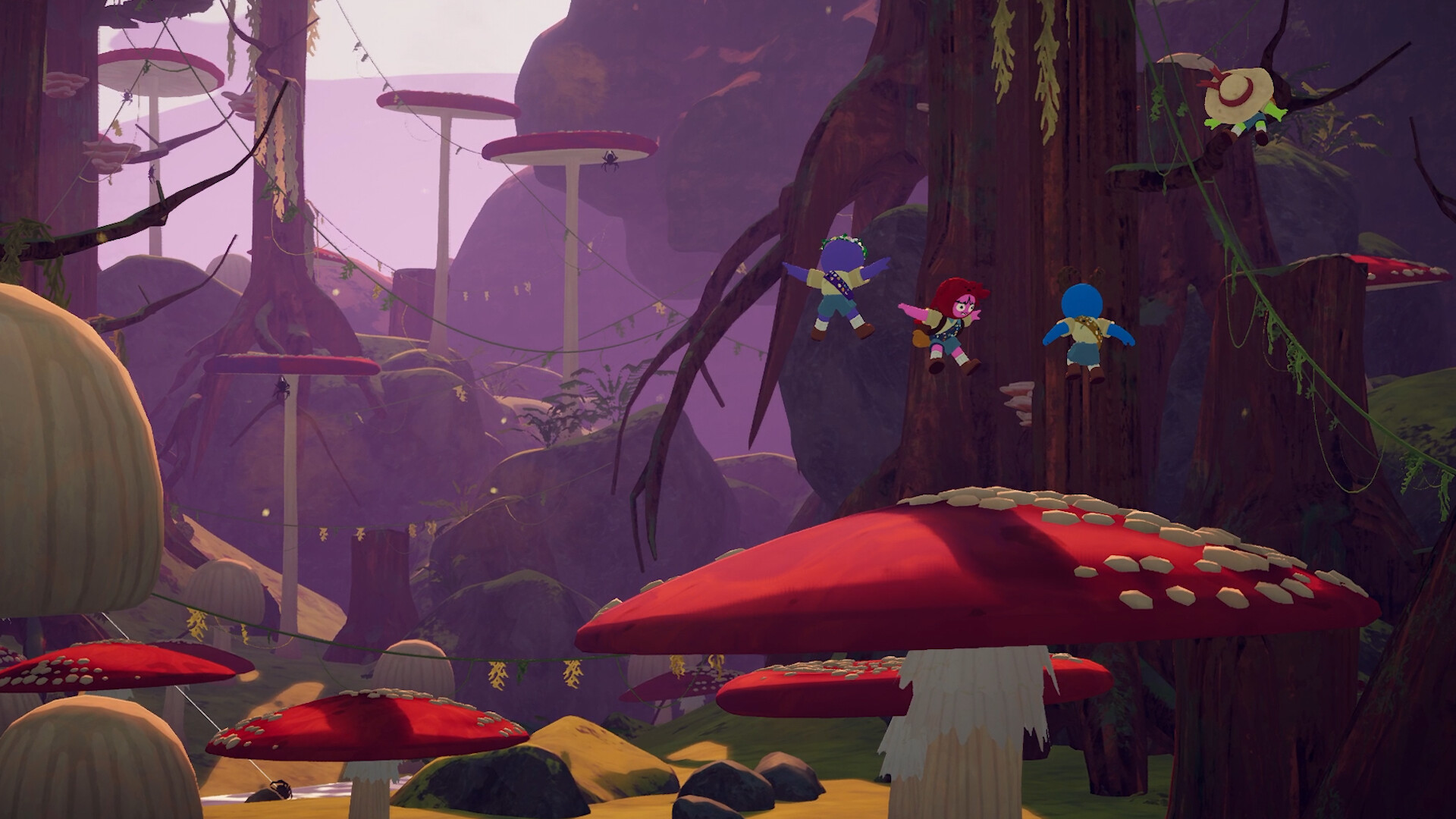

PEAK is deceptively minimal. There are no sprawling skill trees, no complex combat systems, and no traditional progression in the way most modern games define it. Instead, PEAK builds its entire identity around one idea: going up. Every action, decision, and mistake is filtered through the simple but unforgiving logic of verticality.

Rather than presenting climbing as a mechanic, PEAK treats climbing as a condition. Height is not a reward—it is a threat. The higher you go, the fewer mistakes you can afford, and the more you must rely on others. This review explores PEAK as a cooperative survival experience that uses physical space, shared risk, and fragile trust to generate tension, meaning, and memorable failure.

Quick Info (Overview Box)

Release Year: 2024

Genre: Cooperative climbing / Survival

Platforms: PC

Game Modes: Online co-op, small-group survival

Target Audience: Players who enjoy cooperative tension, environmental challenge, and emergent teamwork

1. Core Design Philosophy: Height as Consequence

In PEAK, verticality is not aesthetic—it is existential. Every meter gained increases risk. Falling is not just a setback; it can undo minutes of careful progress or end a run entirely.

This design reframes advancement. Unlike games where progress accumulates safely, PEAK treats progress as temporary. Nothing is secure until the group stabilizes. Height magnifies every error.

The result is a constant background tension. Even during calm moments, the awareness of potential loss shapes player behavior.

2. Movement: Deliberation Over Dexterity

Movement in PEAK is intentionally restrained. Characters do not leap heroically or recover magically from missteps. Grips must be chosen carefully. Momentum matters. Small errors cascade quickly.

This shifts the focus from reflex-based execution to decision-making. Players succeed not by moving fast, but by moving thoughtfully. Rushing is the most common cause of failure.

The game teaches patience through consequence rather than instruction. It never says “slow down”—it lets gravity explain.

3. Cooperative Climbing as a Social Contract

Climbing in PEAK is rarely a solo endeavor. Players rely on each other for positioning, timing, and sometimes literal support.

This creates an implicit social contract. One player’s impatience can doom the group. One player’s hesitation can stall progress. Trust becomes as important as skill.

Unlike competitive co-op games, PEAK does not allow individuals to shine independently. Success is collective, or it does not exist at all.

4. Communication: The Real Gameplay Loop

The most important tool in PEAK is not mechanical—it is communication. Players constantly negotiate routes, risks, and responsibility.

“Wait there.”

“I’m not stable yet.”

“If I fall, move back.”

These exchanges are not flavor—they are survival mechanics. Silence is dangerous. Miscommunication is lethal.

The game quietly transforms voice chat into a core system, making social awareness inseparable from physical progress.

5. Environmental Design: Sparse but Hostile

The environments in PEAK are visually restrained but functionally aggressive. Surfaces differ subtly in grip, stability, and forgiveness. There are few visual cues screaming danger—players learn by experience.

This restraint forces attentiveness. Players scan terrain not for beauty, but for reliability. The environment becomes something to read, not admire.

By avoiding visual clutter, the game ensures that failure feels earned rather than surprising.

6. Failure as the Primary Teacher

Failure in PEAK is frequent and often brutal. Falls happen suddenly. Recovery is limited. The game does not soften the emotional impact.

Yet failure is also the primary learning mechanism. Each fall teaches spacing, timing, or restraint. Players adjust routes, reorder climbing sequences, and assign roles more carefully.

Importantly, the game does not shame failure. It presents it as information. Progress comes from understanding why things went wrong.

7. Player Psychology: Stress, Responsibility, and Guilt

One of PEAK’s most striking qualities is how it distributes emotional weight. When someone falls, the group feels it. Guilt spreads. Blame is often internal rather than external.

Players replay decisions aloud: “I shouldn’t have moved.” “I pushed too fast.” “We should’ve waited.”

This creates a shared emotional space rarely achieved in cooperative games. PEAK makes responsibility collective, not individual.

8. Pacing: Slow Progress, Sudden Collapse

PEAK’s pacing is defined by contrast. Long periods of careful, methodical climbing are punctuated by sudden, irreversible failure.

This rhythm keeps tension high even during quiet moments. Players know that collapse is always one mistake away.

The game avoids artificial escalation. There are no timers or enemy waves. The environment alone sets the pace—and it is unforgiving.

9. Limitations of Variety and Longevity

PEAK’s focused design is also its limitation. The core loop changes little over time. There are no dramatic mechanical twists or content explosions.

The experience relies heavily on group dynamics. With the same group, patterns can emerge. With different players, the game feels fresh again.

Longevity depends not on systems, but on people. PEAK is a game you return to with friends, not one you grind alone.

10. What PEAK Ultimately Represents

PEAK is not about reaching the top. It is about how you attempt to do so. It examines trust under pressure, patience under risk, and communication under fear.

It strips away spectacle and progression to expose something raw: cooperation when failure has real weight.

Few games are willing to be this narrow, this demanding, and this honest.

Pros

Strong cooperative tension built on shared risk

Movement rewards patience and planning

Communication is deeply integrated into gameplay

Failure feels meaningful rather than arbitrary

Minimalist design reinforces focus

Cons

Limited mechanical variety

High dependence on cooperative partners

Not well-suited for solo play

Steep emotional pressure for some players

Repetition with the same group over time

Conclusion: A Game About Holding Each Other Up

PEAK succeeds because it understands that climbing is not just a physical act—it is a social one. Every ascent is a negotiation. Every step upward is a shared risk.

For players who value cooperation, tension, and experiences that emerge from human behavior rather than scripted systems, PEAK offers something rare and powerful. It is not about victory screens or rewards.

It is about the moment when everyone stops moving, holds their breath, and trusts each other to not fall.