Escape the Backrooms – Liminal Fear, Cooperative Fragility, and Horror Without Resolution

Introduction: When Space Itself Becomes the Enemy

Escape the Backrooms is not a horror game about monsters in the traditional sense. It is a horror game about being trapped inside an idea. The idea is liminality: endless, empty spaces that feel familiar yet fundamentally wrong. There is no heroic arc, no escalating power fantasy, and no promise that understanding will lead to safety. The horror does not chase you constantly—it waits.

Escape the Backrooms takes internet myth and transforms it into an experiential horror framework built on isolation, spatial disorientation, and fragile cooperation. It does not overwhelm players with mechanics or narrative exposition. Instead, it weaponizes emptiness, repetition, and uncertainty. This review examines Escape the Backrooms as an exercise in environmental horror, cooperative stress, and how fear emerges when meaning is deliberately withheld.

Quick Info (Overview Box)

Release Year: 2022

Genre: Cooperative psychological horror / Exploration

Platforms: PC

Game Modes: Online co-op, Solo exploration

Target Audience: Players who enjoy atmospheric horror, liminal spaces, slow-burn tension, and cooperative survival under uncertainty

1. Core Design Philosophy: Horror Through Absence

The most important design choice in Escape the Backrooms is restraint. The game removes nearly everything players rely on for comfort: clear objectives, reliable landmarks, predictable pacing, and narrative clarity.

The Backrooms are not dangerous because they are loud or violent—they are dangerous because they are empty. Hallways stretch endlessly. Rooms repeat with slight variations. Familiar office elements lose their meaning through repetition.

This absence forces players to confront fear without stimuli. There is nothing to fight, nothing to master, and often nothing to explain what went wrong. The environment itself becomes hostile simply by refusing to make sense.

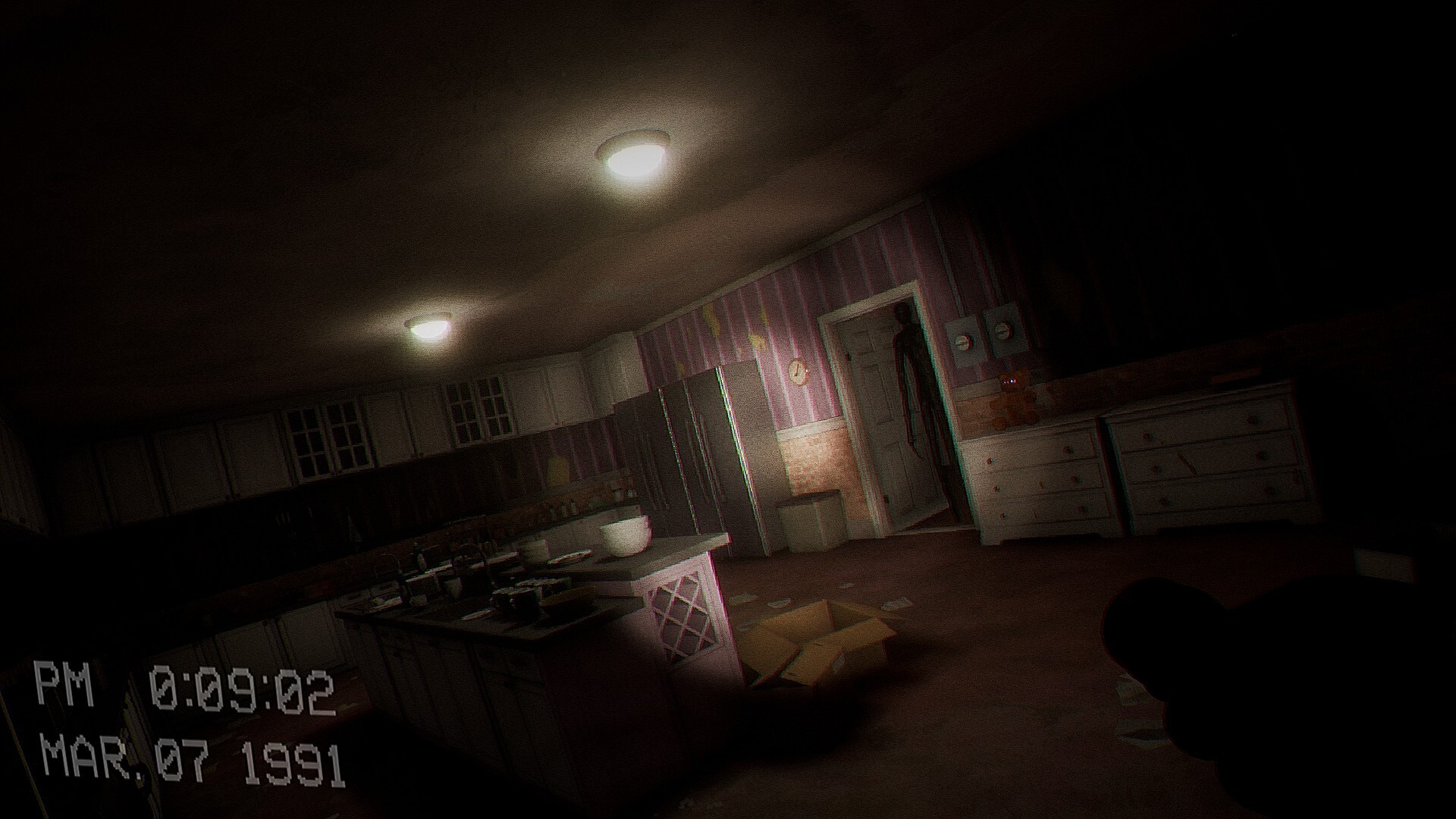

2. Liminal Space as a Psychological Weapon

Escape the Backrooms understands the psychological power of liminal spaces—transitional areas that exist between destinations. Offices after hours, empty hallways, fluorescent lighting with no windows.

These spaces trigger discomfort because they suggest purpose without presence. Someone should be here. Something should be happening. But nothing is.

The game amplifies this unease by extending time spent in these areas. Players do not pass through liminal spaces—they are stuck inside them. The longer you remain, the more reality feels unstable.

3. Exploration Without Reward

Most games reward exploration with loot, lore, or progression. Escape the Backrooms offers exploration without reassurance.

You may find a key, a door, or a note—but these rarely explain more than they reveal. Progress feels temporary and fragile. Advancing often leads to deeper confusion rather than clarity.

This design subverts player expectation. Exploration is no longer empowering; it is risky. Curiosity becomes a liability rather than a virtue.

4. Cooperative Play: Safety That Can Break

In co-op mode, Escape the Backrooms initially feels safer. Hearing another voice, seeing another person, sharing reactions—all provide emotional grounding.

But this safety is unstable. Players can get separated. Communication breaks down. Panic spreads. When one player makes a mistake, others often pay the price.

Cooperation becomes a double-edged sword. Teammates provide reassurance—but also distraction, noise, and shared vulnerability. Trust matters, but trust alone cannot guarantee survival.

5. Communication Under Stress

Voice communication in Escape the Backrooms is constant and revealing. Players narrate fear, confusion, and second-guessing in real time.

“Have we been here before?”

“I think this is new… or maybe not.”

“Wait—where did you go?”

These exchanges are not scripted—they are emergent expressions of spatial anxiety. Communication helps orientation, but also exposes uncertainty. Hearing fear in another person’s voice often intensifies your own.

The game does not punish silence—but silence quickly becomes terrifying.

6. Entities: Fear Through Infrequency

When entities appear in Escape the Backrooms, they are effective precisely because they are rare. The game does not flood players with threats. It introduces danger sparingly, often without clear rules.

Players may not understand what triggered an encounter. Was it sound? Movement? Time? Proximity? This uncertainty makes every decision feel risky.

Entities function less as enemies and more as interruptions. They break the illusion of safety just enough to ensure paranoia never fades.

7. Sound Design and Sensory Manipulation

Audio is one of Escape the Backrooms’ strongest tools. The hum of fluorescent lights, distant footsteps, muffled echoes, and sudden silences create constant low-level tension.

Sound rarely confirms safety. It only suggests presence—or absence. The environment feels alive not because it moves, but because it breathes.

The lack of musical cues prevents emotional regulation. Players cannot rely on audio to tell them when danger begins or ends. Fear has no clear boundaries.

8. Player Psychology: Disorientation and Self-Doubt

One of the game’s most unsettling effects is how it erodes player confidence. After long sessions, players begin to doubt their own memory.

“Did we already check this hallway?”

“I swear this room was different.”

The game does not confirm or deny these suspicions. It allows self-doubt to fester. Orientation tools are minimal, forcing reliance on imperfect human memory.

This psychological erosion is slow and subtle—but deeply effective.

9. Progression Without Mastery

Escape the Backrooms offers progression in the sense that players move through different levels—but not in the sense of growing stronger or more capable.

There are no upgrades. No abilities. No reliable tactics that guarantee success. Knowledge helps, but only temporarily. Familiarity reduces fear slightly, but never removes it.

This prevents mastery from becoming a shield. The game remains threatening even after hours of play.

10. Limitations and Intentional Friction

Escape the Backrooms is not universally appealing. Its pacing is slow. Its mechanics are sparse. Its rewards are abstract.

Players seeking action, clear objectives, or narrative resolution may find it frustrating. Repetition is intentional, but can feel exhausting rather than immersive.

These limitations are not accidental. They are consequences of a design committed to discomfort rather than satisfaction.

Pros

Strong use of liminal space and environmental horror

Cooperative play enhances psychological tension

Effective restraint in enemy and sound design

Disorientation and uncertainty are consistently maintained

Horror emerges naturally rather than through spectacle

Cons

Slow pacing may deter action-oriented players

Limited mechanical variety

Progress can feel unclear or unrewarding

Repetition may exhaust some players

Experience relies heavily on player mindset

Conclusion: Horror That Refuses to Explain Itself

Escape the Backrooms is not a game about winning. It is a game about enduring. It does not reward confidence—it dismantles it. It does not explain fear—it sustains it.

For players who appreciate psychological horror, liminal spaces, and cooperative experiences where uncertainty is the core mechanic, Escape the Backrooms offers a uniquely unsettling journey. It does not rely on jump scares or gore. It relies on emptiness, repetition, and the quiet terror of being somewhere that should not exist.

You are not hunted because you failed.

You are hunted because you are there.